There have been a number of new subscribers lately so I thought I would share a welcome message for those new to the newsletter.

I’m Joel. My goal is to make beautiful, human-scale neighborhoods available to the millions of Americans who want to live in them but currently can’t.

This purpose of this newsletter is to explore:

The fundamental reasons why the type of urban environment most people prefer isn’t more widely available

How to create more of those environments both specifically (we are building a company whose mission it is to do this) and generally by understanding the invisible forces that shape our built environment.

I call the newsletter the Jambalaya because I also tend to get interested in lots of weird things, like that time a few weeks ago I wrote about the end of the last ice age. For some reason, I enjoy sharing these weird things with people on the internet, thus the Jambalaya.

Today, to give new readers a taste of the Jambalaya, I thought I would try to poke holes in my one of my own beliefs. As Charlie Munger says:

“Any year that you don’t destroy one of your best-loved ideas is probably a wasted year.”

and:

“I never allow myself to hold an opinion on anything that I don't know the other side's argument better than they do”

These strike me as very sensible personal rules to follow, but they also make for a good writing prompt. Let’s jump in.

Why Don’t More People Live in Nice, Walkable Places?

One of my deeply held beliefs is that the number of Americans who want to live in beautiful, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods is greater than the availability of those neighborhoods.

In the United States, over half of people (sometimes closer to 80% if you ask a young crowd) say they prefer to live in this:

Or this:

Or this:

but most people actually live in this:

Why is that? Why is there such a huge gap between what type of environment people say they prefer to live in and the type of environment they actually live in?

The laws of economics tell us that if that many people demand it, the market should have supplied it already. So maybe what people say and what they actually want are two different things? Maybe surveys are wrong and people don’t actually want to live in places where they can walk more and drive less?

I think the answer isn’t that there is a difference between people’s stated and revealed preferences, but that there are a number of structural factors that simply make good urban environments unattainable to all but a small number of Americans. Here are the two that I think have the biggest impact.

Zoning & the Auto-Dependence Cycle

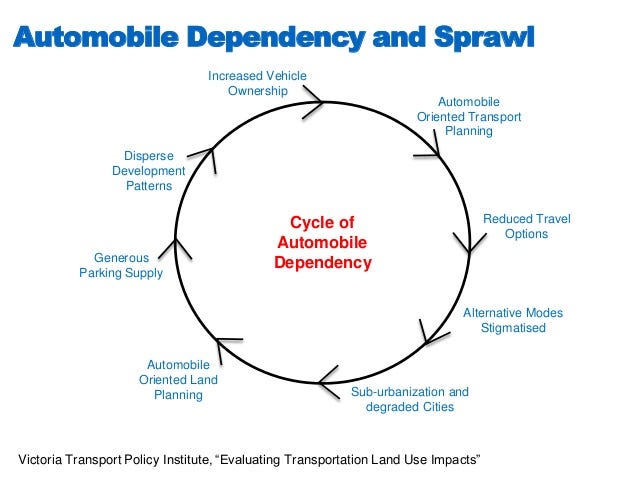

To understand why the US looks the way it does, all that’s really needed is this diagram:

Breaking the Cycle of Automobile Dependency

The especially vicious part of the cycle is that this pattern got encoded in zoning regulations over the 20th century. Parking minimums, density maximums, land use requirements, and all kinds of other rules not only influence the types of things that can be built, but influence how those who build places think about building.

Well, how did we make them illegal to build? Here’s a little about single-use zoning, probably the largest single driver of auto-dependent development:

One of the biggest reasons many cities aren’t walkable is because land is dissected into “uses,” something called “single-use zoning”: Retail cannot be next to a medical office cannot be next a single-family home cannot be next to a multi-family home. So in order for a person to get lunch, go to the doctor, and then buy a birthday present, they have to travel to three different “zones,” and can only do so efficiently by car. This may have been helpful in the 19th century when homes needed to be far away from factories emitting toxic fumes, but today it makes less sense.

Why walkable cities are good for the economy, according to a city planner

Some places have taken steps to roll back these laws. But regulations, once in place, become calcified and difficult to change. Even if changed, they remain part of the fabric of how everyone thinks, and therefore builds.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it” - Upton Sinclair

Once developers start building shopping centers with massive parking lots and 50,000 square foot retail stores (and making a lot of money doing it), it becomes an uphill battle to do anything else. Inertia is a powerful and mostly invisible force, and it always pushes people into doing what is familiar.

Further, development is a complex business with a lot of borrowed money and therefore very low tolerance for experimentation. If building those shopping centers works, by George, we’re not going to risk trying something else!

To sum up: the first reason these walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods are undersupplied is because a combination of:

1. The auto-dependence cycle

2. Outdated but persistent zoning regulations

3. Developer risk-aversion (copy what works)

Makes those neighborhoods extremely difficult or often impossible to build. In economics terms, there is strong demand for them but the supply is inelastic - it can’t easily be expanded to meet demand.

For those who took economics, you know what happens when demand increases and supply remains fixed…

Priced Out

Walkable, mixed-use places are the most expensive areas of the country to live in, full-stop. Manhattan is both the most walkable and most expensive part of the United States.

“An increase in Walk Score from 19 to 20 resulted in a home price increase of about $181 on average across the metros. On the other hand, moving from a location with a Walk Score of 79 to that with a score of 80 resulted in a home price increase of over $7,000. […] The price premiums accelerate even more as the Walk Score gets closer to 100, implying high demand relative to supply for homes in high scoring city areas.”

How Much is a Point of Walk Score Worth?

Why is it so expensive to live in these places? First, what do we mean by expensive?

One acre of central land in New York City is worth approximately 72 times more than an equivalent acre of central Atlanta or Pittsburgh, and almost 1,400 times more than the Rust Belt and Sunbelt metro equivalent land.

Study shows huge disparity in U.S. urban land value, with NYC making up 10%

This is obvious when you think about it. The cost to construct a new building in New York City isn’t 1,400 times more expensive than in the Sunbelt. The cost to own a piece of land is where this disparity arises.

In the most expensive real estate markets it is land, not construction, that accounts for a majority of the cost to live there.

Why the Difference?

Urban land is so expensive because it is proximate to stuff. Job opportunities, dating markets, daily essential goods and services, culture, entertainment, and so on. For more on this, see this article.

Suburban land is so cheap because it isn’t proximate to anything. All else equal, people prefer to be close to things than far away from them because it makes daily life easier and more pleasant. Here’s Jane Jacobs describing the proximity effect in cities:

Proximity is the vital ingredient that makes all urban areas tick. It is this proximity that enables people to exchange ideas, goods, fashion, beliefs, knowledge and anything else they see fit, generating the diversity that the most valued places all share. It is when people come together that mankind's greatest achievements and most engaging environments have been realised. And it is when this proximity is diluted that the success of urban areas is most harmed.

Saying a neighborhood is walkable or mixed-use is just another way of saying it offers proximity. Because places like Manhattan offer proximity to just about everything, the value of the land there is very, very high. So, mixed-use places with lots of proximity to stuff tend to be expensive to live in.

The land values in these places are astronomical. This increase in land value isn’t a problem in itself. The problem arises from the fact that only a small number of people can afford to purchase land in these areas. The rest of the people who live there - who create land value through their daily activities but do not own property - do not capture any of the increase in value.

Those who don’t own land in these areas are left out of the wealth creation process and eventually become priced out of the market as the rents demanded by landowners rise above what their wages can pay.

Is it possible to have our cake and eat it too? Can we create places where people live in nice, mixed-use environments with most of their daily needs in proximity, while also maintaining reasonable land values? I think so, and we’ll get into how to do that in future newsletters.

For now, we just need to understand is that when a location provides people with access to lots of stuff like jobs, culture, goods and services, it tends to become very expensive to live there. This effect is the second reason that walkable, mixed-use places are off-limits to all but a handful of Americans.

Conclusion

“In theory there is no difference between theory and practice - in practice there is.” - Yogi Berra

In theory, consumer demand should pull real estate developers to build more mixed-use, human-scale development.

In practice, however, in most US cities, inertia, regulation, and developer risk-aversion conspire to make that difficult or impossible.

Second, when there are pockets of walkable/mixed-use neighborhoods that do exist (usually because they were built before single-use zoning laws existed) they are too expensive for the vast majority of people to live in.

It’s clear that people want to live in these environments. It’s also clear that they won’t be built on their own. That’s what creates the urgency I feel to try to build more of them, while also addressing some of the shortcomings of current municipal, ownership and development models.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this welcome edition of the Jambalaya and learned a little about how I think about some of these topics. If you’re interested in receiving these emails more often, you can enter your email below to get future updates.

Until next week,

Joel

Fantastic summary, Joel!