Subvert, always subvert

Put away your dictionaries

This week’s Jambalaya is a day late as we just got back from a trip to the Gulf Coast. It’s beautiful down there, and whenever I’m near the ocean I tend to think about weird stuff. So in the spirit of the ocean and in keeping this a real Jambalaya - a mixture of truly random things - I will share a paleoclimatology fact that I find incredible:

Everyone knows about the glaciers that covered huge parts of the Earth during the last Ice Age. The sheets covered about 8% of the world’s total surface and about 25% of all the land. But here’s something I didn’t know until recently: during the peak of the last Ice Age, sea levels around the world were about 400 feet lower than they are today.

As the glaciers melted, sea levels rose around the world, submerging about 10% of the world’s total land mass. The Earth looked very different with all that water locked up in glaciers. Here’s the coastlines of the Southern United States and Central America/The Caribbean:

Florida put on some weight!

If you look closely you can see that the The Bahamas, today a chain of mostly tiny islands, was once a very large landmass. The Gulf Coast and the Yucatán Peninsula were also substantially larger.

I just think it’s so cool that such huge amounts of the world were submerged. Scientists have found that stories of this global flooding have been passed down through oral histories of humans living in areas affected by it. It seems like there could be some cool stuff waiting to be discovered underwater that could tell us a lot about human civilization.

Invert, Always Invert

The idea I want to share in this issue is a variant of the “Invert, always invert” mantra that Charlie Munger often cites.

What he means is that some problems are difficult to solve in one direction, but easy to solve when turned around in the opposite direction.

A common example is health: It’s easier to figure out what is bad for your health and avoid it than it is to do it in the positive. “What is good?” is a harder question to answer than “What is bad?”. Similarly, it’s easier to be virtuous by avoiding the “Seven Deadly Sins” than it is by “being good”. What does it mean to be good? It often depends. Bad behavior, on the other hand, is usually pretty easy to identify and avoid.

Munger often sums it up with the funny phrase:

All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there.

Inversion is about figuring out what will kill you and then avoiding it. It’s a great tool to carry with you through life. Here’s the rhyming cousin of it that I propose.

Subvert, Always Subvert

Confession time: in the process of writing this I’ve come to find out that subvert doesn’t mean exactly what I thought it meant. Turns out my vocabulary isn’t that great. The official definition is to “undermine the power or authority of an existing institution.”

But that’s not really what I’m trying to say. The idea I’m trying to describe is that when it comes to big problems, they should not be attacked head on, but rather come at indirectly, possibly at an angle that isn’t at all obvious. Don’t approach with a head-on charge, try to flank it.

A more accurate way of saying it is “always approach big problems obliquely rather than head on”. But that’s not nearly as catchy, so please put away your dictionary and let’s continue using the “Subvert, always subvert” phrase.

Take housing as an example. Attacking the problem head on is the very rational, logical way of approaching it. And that’s exactly why it won’t work.

I will call this the political approach. Political approaches to problem solving are always logical. They make a lot of sense. Politicians can’t make too many people upset, so everything they do must sound very reasonable.

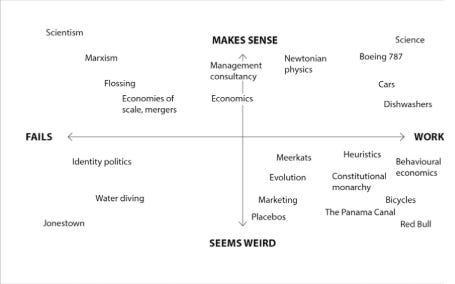

But not everything that makes sense works, and not everything that works makes sense. Here’s an entertaining chart from Alchemy by Rory Sutherland:

Just like nobody was ever fired for buying IBM, no politician is ever given a hard time for solutions that sound reasonable (at least from their own party).

“If you do anything counter-intuitive and it doesn’t work, the extent to which you get blamed for it is 10 times greater than if you do something seemingly logical that doesn’t work.” - Rory Sutherland

So the logical solutions persist.

People can’t afford to buy houses? Well, give them some extra money to buy houses! Boom. Politically solved.

Cities don’t allow enough new housing to be constructed? Incentivize them with cash to modernize their zoning codes! Boom. Politically solved.

This just feels like the modern medicine approach applied to politics: completely ignore the underlying disease while prescribing side-effect heavy medicine to make the patient temporarily feel better.

The problem with logical solutions is they always get you to the same, logical place. It’s impossible to solve problems using the same thinking that created them, and all that.

Here’s Scott Alexander from his “Meditations on Moloch” article about how incentives shape systems:

Any human with above room temperature IQ can design a utopia. The reason our current system isn’t a utopia is that it wasn’t designed by humans. Just as you can look at an arid terrain and determine what shape a river will one day take by assuming water will obey gravity, so you can look at a civilization and determine what shape its institutions will one day take by assuming people will obey incentives.

But that means that just as the shapes of rivers are not designed for beauty or navigation, but rather an artifact of randomly determined terrain, so institutions will not be designed for prosperity or justice, but rather an artifact of randomly determined initial conditions. Just as people can level terrain and build canals, so people can alter the incentive landscape in order to build better institutions. But they can only do so when they are incentivized to do so, which is not always. As a result, some pretty wild tributaries and rapids form in some very strange places.

You can’t blame politicians for proposing solutions like this much more than you can blame a river flowing a certain path through a canyon. It’s not necessarily the will of the politician or river - it is inherent in the structure of the system they both exist in. Incentives always win out in the long run.

Trying Weird Things

So I use these examples not to complain, but instead to think about a different way to solve these problems. What I mean to say with the “subvert, always subvert” mantra above is when thinking about problems like this, it’s necessary to think about how they might be approached indirectly. Ideally by standing outside the current systems and incentive structures.

Is that easy to do? Of course not. But it’s what’s needed to develop to tackle these problems.

Instead of just subsidizing first time homebuyers, shouldn’t we try to figure out why first time homebuyers can’t afford homes? Instead of pushing cities to change their zoning, shouldn’t we be sure we understand where the affordability problem really is?

If you want to discover great new things, then instead of turning a blind eye to the places where conventional wisdom and truth don’t quite meet, you should pay particular attention to them. - Paul Graham

I don’t think the conventional wisdom and truth around housing/land use really meet today, so I think it’s an area worth paying particular attention to. The political approaches mentioned above are a start, but I just can’t shake the feeling that they’re missing something more fundamental. It seems like the perfect area to start trying some unconventional things. Silly things; things that maybe even make people laugh when they first hear them. Here’s Paul G again:

The second component of independent-mindedness - resistance to being told what to think - is the most visible of the three. But even this is often misunderstood. The big mistake people make about it is to think of it as a merely negative quality. The language we use reinforces that idea. You're unconventional. You don't care what other people think. But it's not just a kind of immunity. In the most independent-minded people, the desire not to be told what to think is a positive force. It's not mere skepticism, but an active delight in ideas that subvert the conventional wisdom, the more counterintuitive the better. Some of the most novel ideas seemed at the time almost like practical jokes. Think how often your reaction to a novel idea is to laugh. I don't think it's because novel ideas are funny per se, but because novelty and humor share a certain kind of surprisingness. But while not identical, the two are close enough that there is a definite correlation between having a sense of humor and being independent-minded — just as there is between being humorless and being conventional-minded.

To paraphrase Rory Sutherland again, stubborn problems are stubborn probably because they are logic-proof. If they weren’t, they would have already been solved by logical means. If the solution to high housing prices was logical - say, legislation like rent control - it would have long ago been solved.

I’ll do some more writing soon on what I think some of the more fundamental problems and solutions might be in this space, but I hope this issue at least prompted some thinking about how to question the conventional solving of problems.

In rereading Paul Graham’s essays the last few days I’ve come across a few other gems that are somewhat related, so I’ll leave those below for you to enjoy. His writings are a constant source of inspiration and enjoyment. Until next week,

Joel

On procrastination as a way to do great work:

The most impressive people I know are all terrible procrastinators. So could it be that procrastination isn’t always bad? There are infinite number of things you could be doing. No matter what you work on, you’re not working on everything else. So the question is not how to avoid procrastination, but how to procrastinate well. There are three variants of procrastination, depending on what you do instead of working on something: you could work on (a) nothing, (b) something less important, or (c) something more important. That last type, I’d argue, is good procrastination. That’s the “absent-minded professor,” who forgets to shave, or eat, or even perhaps look where he’s going while he’s thinking about some interesting question. His mind is absent from the everyday world because it’s hard at work in another. That’s the sense in which the most impressive people I know are all procrastinators. They’re type-C procrastinators: they put off working on small stuff to work on big stuff. Good procrastination is avoiding errands to do real work. Good in a sense, at least. The people who want you to do the errands won’t think it’s good. But you probably have to annoy them if you want to get anything done. The mildest seeming people, if they want to do real work, all have a certain degree of ruthlessness when it comes to avoiding errands.

On ambitious things:

Even the most ambitious people shrink from big undertakings. It’s easier to start something if one can convince oneself (however speciously) that it won’t be too much work. That’s why so many big things have begun as small things. Rapid prototyping lets us start small

On tackling big problems indirectly:

Let me conclude with some tactical advice. If you want to take on a problem as big as the ones I've discussed, don't make a direct frontal attack on it. Don't say, for example, that you're going to replace email. If you do that you raise too many expectations. Your employees and investors will constantly be asking "are we there yet?" and you'll have an army of haters waiting to see you fail. Just say you're building todo-list software. That sounds harmless. People can notice you've replaced email when it's a fait accompli

Empirically, the way to do really big things seems to be to start with deceptively small things. Want to dominate microcomputer software? Start by writing a Basic interpreter for a machine with a few thousand users. Want to make the universal web site? Start by building a site for Harvard undergrads to stalk one another.

Empirically, it's not just for other people that you need to start small. You need to for your own sake. Neither Bill Gates nor Mark Zuckerberg knew at first how big their companies were going to get. All they knew was that they were onto something. Maybe it's a bad idea to have really big ambitions initially, because the bigger your ambition, the longer it's going to take, and the further you project into the future, the more likely you'll get it wrong.

I think the way to use these big ideas is not to try to identify a precise point in the future and then ask yourself how to get from here to there, like the popular image of a visionary. You'll be better off if you operate like Columbus and just head in a general westerly direction. Don't try to construct the future like a building, because your current blueprint is almost certainly mistaken. Start with something you know works, and when you expand, expand westward.

The popular image of the visionary is someone with a clear view of the future, but empirically it may be better to have a blurry one.

Treating and focusing on symptoms, not the underlying ailment. Yes. Everything from gun violence to national security policy seems to be caught in this vortex. Is it the political expediency (and popularity) of easing the temporary situation (symptom) that causes this short-sighted approach to policy?

You are writing GEMS Joel!!! Loved this one. I’ve often called myself an “unconventional” urban planner because of my distrust for the dogma of the profession. Now, independent-mindedness is a mouthful but much more accurate and positive too!

I also think it’s time for the word “subvert” to broaden up a bit. Maybe it’s not about authorities... but long-standing, enduring, perennial problems can be almost equally as crushing, almost more, because our reason for not being able to solve them is ourselves. We can be made aware of our blind spots, but society pursues this more as a hobby rather than a moral imperative. Well, keep on fighting the good fight Joel.