Controlling the Conditions of Your Life

How to Measure the Quality of a Resident's Experience

For all my recent ranting and raving about the importance of a great Resident Experience, I have had a hard time nailing down just how you would measure whether a place does a good job of providing it.

That all changed when I recently re-read the fantastic The Lessons of History by Will and Ariel Durant.

It hit me when I read the authors’ definition of progress:

We shall here define progress as the increasing control of the environment by life. It is a test that may hold for the lowliest organism as well as for man… Our problem is whether the average man has increased his ability to control the conditions of his life.

As vague as this sounds, it’s actually a very powerful explanation of which places provide a great Resident Experience and which don’t.

We can ask: “To what degree is a person living in this environment able to control the conditions of her life?”

From there, we can make some definite measurements. How much is a person in that environment spending on housing costs? Every dollar unnecessarily spent on housing costs is a dollar not spent pursuing other ends that the individual chooses.

In other words, the more someone spends on housing, the less they are able to spend controlling other conditions of their life. Higher housing costs = regression, not progress.

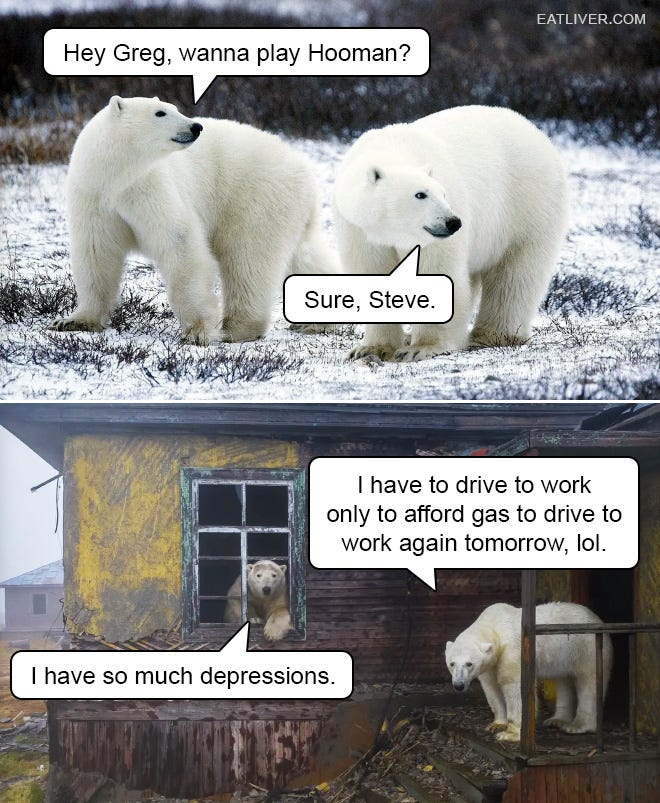

As another example, every minute spent driving because of low-quality, energy intensive car dependent design in an expensive vehicle is a minute not spent with a spouse, children, or friends. It’s also income spent on poor design that could be spent elsewhere - again, controlling other conditions of one’s life.

Certain urban configurations give those who live in them the power to control the conditions of their lives. Others do the exact opposite.

People often dismiss arguments for better built environments by saying “well that’s just an aesthetic preference.”

The Durants’ definition of progress when applied to real estate and urban design shows us that this argument simply isn’t true.

When each person lives in an environment (photo 2) that requires ownership of a $12,000+ per year vehicle to do things as basic as acquire food or see another human, they become dramatically less able to control the conditions of their life.

On the other hand, a person who can walk out their front door when they choose and visit friends, shop, get food, or a number of other things at little to no cost (Environment #1) has an incredible amount of control over the conditions of their life.

Environment #2 is like in elementary school when in order to go to the bathroom, you must politely ask for the hall pass in order to leave the classroom. Except the hall pass costs $12,000 per year and might kill you. As an adult, you just get up and go to the bathroom.

The adult is more able to control the conditions of her life than the child. So too is the Resident of Environment #1 more able to control the conditions of her life than the Resident of Environment #2.

So environment #1 pictured above is pretty, sure, but in the Durants’ framing it’s also progress in the sense it gives the people who live and visit it more control over the conditions of their life. Environment #2, while more recently built, represents a horrible regression in this regard.

Couple that with spending 6-12 times household income on a home (compared to more normal historical range of 2-4 times) and millions of people living in American cities today have less ability to control the conditions of their life than in much of our country’s history.

Progress is an improvement in the means that we use for achieving the same old ends. I sometimes wonder if whether the progress is only of means without any progress in ends. - The Lessons of History

In the Durants’ framing, millions of Americans today pursue the same ends1 as ever but at much greater expense, inconvenience, and general despair.

Every dollar spent on transport or housing is a dollar not spent starting a business, saving for your kids’ future, indulging in a hobby that brings you joy, donating to charity, or a million other things you might choose.

Further, many people have to work more just to afford housing, leading to a loss of something much more valuable: time. Money spent unnecessarily on expensive housing rather than a child’s education is a problem, to be sure. Time spent working to afford housing instead of with a child is not just a problem, it’s a tragedy.

If we accept the Durants’ definition of progress above then it leads us to the quite shocking conclusion that although the United States has progressed marvelously in medicine, aerospace, computer science, and much else over the last century, it has regressed terribly in transportation, housing, and the general architecture and design of its cities.

Thanks for reading 😊

Joel

P.S. Here are a few more excerpts from The Lessons of History that I enjoyed:

The present is the past rolled up for action, and the past is the present unrolled for understanding.

Progress is an improvement in the means that we use for achieving the same old ends. I sometimes wonder if whether the progress is only of means without any progress in ends.

The influence of geographic factors diminishes as technology grows. The character and contour of a terrain may offer opportunities for agriculture, mining, or trade, but only the imagination and initiative of leaders and the hardy industry of followers, can transform the possibilities into fact; and only a similar combination can make a culture take form over a thousand natural obstacles. Man, not the earth, makes civilization.

We are the same at birth that we used to be, but in a sense, we progress by the rise of the pedestal of the social heritage.

No one man, however brilliant or well-informed, can come in one lifetime to such fullness of understanding as to safely judge and dismiss the customs or institutions of his society, for these are the wisdom of generations after centuries of experiment in the laboratory of history.

Evolution in man during recorded time has been social rather than biological: it has proceeded not by heritable variations in the species, but mostly by economic, political, intellectual, and moral innovation transmitted to individuals and generations by imitation, custom, or education.

History repeats itself, but only in outline and in the large. We may reasonably expect that in the future, as in the past, some new states will rise, some old states will subside; that new civilizations will begin with pasture and agriculture, expand into commerce and industry, and luxuriate with finance; that thought…will pass, by and large, from supernatural to legendary to naturalistic explanations; that new theories, inventions, discoveries, and errors will agitate the intellectual currents; that new generations will rebel against the old and pass from rebellion to conformity and reaction; that experiments in morals will loosen tradition and frighten its beneficiaries; and that the excitement of innovation will be forgotten in the unconcern of time.

If progress is real despite our whining, it is not because we are born any healthier, better, or wiser than infants were in the past, but because we are born to a richer heritage, born on a higher level of that pedestal which the accumulation of knowledge and art raises as the ground and support of our being. The heritage rises, and man rises in proportion as he receives it. History is, above all else, the creation and recording of that heritage; progress is its increasing abundance, preservation, transmission, and use…If a man is fortunate he will, before he dies, gather up as much as he can of his civilized heritage and transmit it to his children. And to his final breath he will be grateful for this inexhaustible legacy, knowing that it is our nourishing mother and our lasting life.

We should never use the word progress to imply progress in everything. Obviously we are progressing in some things, and retrogressing in others.

If education is the transmission of civilization, we are unquestionably progressing. Civilization is not inherited; it has to be learned and earned by each generation anew; if the transmission should be interrupted for one century, civilization would die, and we should be savages again. So our finest contemporary achievement is our unprecedented expenditure of wealth and toil in the provision of higher education for all…We may not have excelled the selected geniuses of antiquity, but we have raised the level and average of knowledge beyond any age in history.

Consider education not as the painful accumulation of facts and dates and reigns, nor merely the necessary preparation of the individual to earn his keep in the world, but as the transmission of our mental, moral, technical, and aesthetic heritage as fully as possible to as many as possible, for the enlargement of man’s understanding, control, embellishment, and enjoyment of life. The heritage that we can now more fully transmit is richer than ever before.

The ends pursued can be anything: from raising healthy, happy children to leaving a mark on the world to being a pillar of one’s community. In our discussion the ends are irrelevant, what matters is how easy and inexpensive it is for people to pursue whichever ends they select.

When I think of walkability and livability, it can be easy to forgot just how important it is for inclusion and equality. We didn't realize just how important our walkability was until my wife really needed it. It allowed independence at a time that a car couldn't. We have also noticed just how closer knit a community is when it is walkable. That, along with excellent public transit could be a equalizer and game changer for so many. Florence being a university town helps some with these aspects, as many of these basic needs are necessary for students, but imagine what it would be like to have a robust trolley/bus network and a city center that was less car-centric!