Positive Sum Housing Games

"In a tug of war, it's often surprising how far you can go if you tug the rope sideways"

In life, the challenge is not so much to figure out how best to play the game; the challenge is to figure out what game you’re playing.

Kwame Appiah

Should you find yourself in a chronically leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is likely to be more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.

Warren Buffett

Each of the first two great economic revolutions – the Neolithic and the Industrial – were the result of the attempt to develop new techniques for organizing groups of humans and capturing the gains from cooperation.

Michael Munger, Tomorrow 3.0

In my last post I shared about the time that my dad accidentally taught me a fundamental secret about life.

Spoiler if you haven’t read it: the secret is to always seek positive-sum games in life, and whenever possible, to figure out ways to convert seemingly zero-sum situations into positive-sum situations.

This is a lens I use to look at all sorts of things. After some reflection, it struck me that the debate around land value and housing policy (and associated effects of increasingly unaffordable housing) in many major cities sounds an awful lot like a zero-sum game.

I realize I run a substantial risk of developing Man-With-a-Hammer Syndrome, but I hope you’ll indulge me because I think there might be something here. This post is an exploration, not a fully-baked position.

In two posts, I’m going to explore two main questions:

Is land value today really a zero-sum game?

If so, how could we make it a positive-sum game?

Let’s get started.

Is Land Value a Zero-sum Game?

One good test of a zero-sum situation is: What is good for one side is bad for the other, and vice versa.

Cities need to construct new housing to allow more people to live there. There is a fixed amount of land in desirable locations. Building new housing has to involve building at greater densities: building more units of housing on the same amount of land.

If a city allows more density to be built, the narrative goes, the effect in the short to medium term is to bring down housing costs because there is more supply to meet demand of new residents.

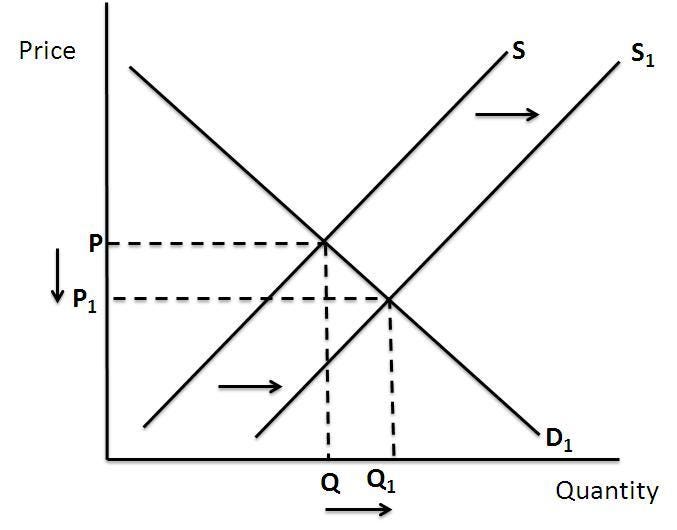

Straight out of Econ 101: Increase supply and all else equal, price decreases:

On the other hand, existing owners of land stand to benefit if the real estate they own increases in value. The most straightforward way to increase the price of something is - assuming demand stays the same - for supply to decline. The only lever with which to reduce the “supply” of land is through the policy of not allowing building at higher densities.

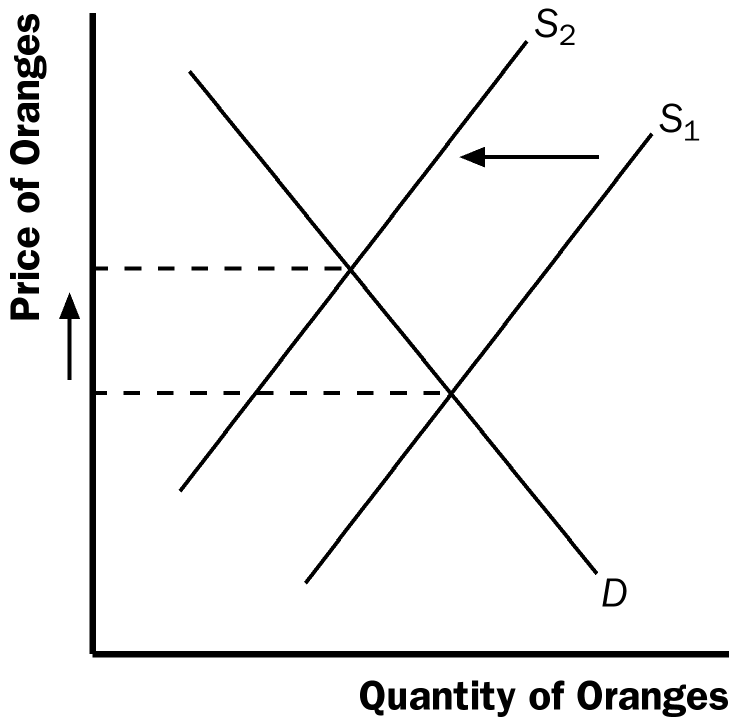

I’m simplifying here, but what happens in econ terms is that existing landowners want the supply curve to shift to the left - the opposite direction. Why? Because this means higher land values for them!

Just substitute “Oranges” for “Housing Units” 😂

And here we come to the zero-sum nature of this problem:

Any rightward shift in the supply curve (more housing built on the same amount of land) is bad for existing landowners and good for new residents and renters.

Any leftward shift in the supply curve (less housing built on the same amount of land) is good for existing landowners and bad for new residents and renters.

Of course there is nuance here. In the long run new housing is actually financially better for existing land owners too because it means more people move to the city, generate economic activity, culture, and innovation. This means, in the long run, the benefits of higher population lead to increased land value even with lots of new housing being built.

But as the joke goes, “In the long run we are all dead.”

In theory these landowners who oppose new development should actually welcome it because in the long run they’re better off. Alas, in practice that is not what happens.

To the landowner, the benefits of building bountiful new housing (if perceived at all) are diffuse, abstract, and far in the future, while the downsides are financially measurable, emotionally charged, and firmly in the near-term.

This is backed up by research - upzoning does reduce housing costs in the short term, which is great!… for half of the players in this zero-sum game:

Research on the greater Boston area by economists at the University of Warwick, the University of Toronto and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston found that the number of housing units rises sharply when density constraints are relaxed — whether by allowing more multifamily buildings, relaxing height limits or simply allowing building on smaller lots. Rents in multifamily buildings fall as much as $144 a month for each new unit added due to the new rules.

The problem is that the value of single-family homes also falls, in part because the added housing weighs on perceived neighborhood quality: House prices drop by 9.17% per unit when density regulations are relaxed and multifamily homes are allowed. “While lowering housing costs through zoning reforms may help first-time homebuyers and lower-income renters,” the economists wrote, “it comes at the expense of — and thus will likely generate substantial political opposition from — current homeowners.”

The US Should Bribe Homeowners to Accept Greater Density

At the risk of stating the obvious, this research makes clear it is impossible to both raise and lower the cost of housing at the same time. One side’s gain is the other side’s loss: Sounds pretty zero-sum to me.

Why would tens of millions of people today, many of whom have their entire net worth in the value of the land underneath their house, voluntarily support any policy that destroys their life? Suddenly they can’t retire, or their kids can’t go to college, or they’re underwater on their mortgage, all because you want to reduce rent by $144 per month for some stranger? Why would these people agree to do that?

Indeed, I think the answer is simply: they won’t agree to do it. Not in a million years. Quite the opposite in fact: they will try to invent policy that does the opposite. There will be temporary wins for new housing-friendly policy, without a doubt. But overall this will continue to be a zero-sum, back and forth nightmare. Not because of human nature, policy, or anything else, but because of the incentives that guide people’s behavior around land value.

To be clear, I think building more housing everywhere is good. But it doesn’t matter what I think. These are forces far stronger than the wishes of any individual or group of people.

The Power of a Positive Sum Game

To see what a positive-sum game would unlock, it helps to consider an example of what happens when we turn a familiar positive-sum game back into a zero-sum game.

Imagine you want to make an investment in a productive company like Apple. But instead of buying shares in Apple the company, you only owned stock in one very particular part of Apple. Say, an Apple retail store. On the surface this may seem similar enough to satisfy your objective.

Let’s imagine you purchase 10% of the equity in that Apple retail store. That means you’re entitled to 10% of everything it owns today (all assets minus liabilities) plus 10% of everything it earns into the future.

If this store is profitable, the value of your shares generally increases over time.

But here’s the problem: your incentives are not well aligned with the company as a whole, and might even be opposed. What is good for your store might end up being bad for the company as a whole, and vice versa.

It might be in your best interest to actively funnel customers away from buying the product they really need and into buying what happens to be in stock in your store. This harms customers, and damages the reputation of the company.

Back to game theory, this turns your economic relationship with Apple from positive sum to zero sum. Every sale that goes to Apple online is a sale that you don’t get credit for.

You as the Apple store owner are locked in a zero-sum battle with Apple the company. Every time a customer visits your store and spends time with a salesperson it costs you money. If they then find out the product they want is only available online, this represents a loss to you. You spent money but earned no revenue.

So you start getting inventive. You devise a plan to hit up all the other Apple store owners and propose a board resolution that gives Apple stores special rights and protections.

Maybe you start trying to charge more in your store to make up for all the sales lost to online. Maybe you add on some extra “service fee” to each purchase to boost margins. Each action is an attempt to take more from the now-fixed pie of “customer purchases from Apple” for your retail store. These are classic zero-sum strategies - trying to modify the rules of the game (some might call it cheating) to give your side an advantage.

One funny/sad thing about zero-sum games: they channel the immense creativity and problem-solving capacity of the human mind into finding better ways to destroy the other side and win the fight. The best thing about positive-sum games is they channel the same human ingenuity into more useful ends.

Who suffers the most? The customer. Before too long, the whole thing has gone to shit. You see Apple the company and your customers not as people to be served, but resources to be exploited for as much as possible. Customers feel this, and start looking for other places to get electronic devices.

You may have won a zero-sum game of securing more resources for your store (as your incentives have guided you to do), but you’ve lost the larger positive-sum of building a great company because of this misalignment.

But imagine for a second that instead of buying shares in that particular retail store, you purchase shares in Apple as a company.

Suddenly, everything is different. You don’t give a shit how the Apple stores do as long as they’re enhancing the overall value of the business. They could even operate at a loss but provide such a great user experience that the overall value of the business grows.

Your incentives are now aligned with Apple’s managers and other shareholders. Everyone is rowing in the same direction.

Give People Stock in the Damn Thing

The technology that makes this miraculous incentive alignment possible did not always exist. The corporation was a human invention. A soft, “social technology”, but a technology nonetheless:

The primary invention of the corporation was to treat a group of people as a single person under the law. For the next five hundred years, corporations were created by government charter. But by the mid- 1800s, the industrial revolution revealed their limitations. By 1900 a series of innovations had created what might be called Corporation 2.0. Anyone could now create a company, the corporation had limited liability, and the assets of the company were separate from its owners.

The corporation is a social technology that makes it easy for anyone to start or play a positive-sum game.

When it became possible for anyone to create a company, it unlocked an enormous amount of Creative Destruction that has propelled the economy for, depending on who you ask, a few centuries (and still is!)

A big part of the magic of the corporation is bundling all assets, liabilities, and the right to future cash flows into a single “thing” called a corporation, and then letting individuals own pieces of that rather than pieces of the individual assets, liabilities, and cash flows.

This one weird little trick™️ of abstraction makes incentive alignment possible on a previously unimaginable scale. Not only does it mean thousands of people can work together towards a common goal, but that they do so voluntarily!

The importance of ownership is hard to overstate. A corporation can create mission statements, vision statements, feel-good retreats that preach “teamwork” all it wants, but until it gives some people stock in the damn thing, none of it will matter. You can create some alignment by paying high salaries, but you will not get the best out of people, nor attract the best people in the first place.

Asking home/landowners to support pro-housing policy is like starting a company and asking people to work 80 hours a work for three years for minimum wage without giving them any ownership. Maybe you find one or two weirdos who are willing to do that, but your chance of success is dramatically lower than an equivalent company that gives people ownership.

Trying to build an innovative company or deliver a great product without stock-based compensation is like trying to win a fight with both arms tied behind your back.

Similarly, trying to solve the housing crises without realigning the incentives of the people involved in it is equally hopeless.

No amount of policy change, master planning, or strong leadership will suddenly make everyone in a city cooperate toward a common goal. For that we need different incentives.

But don’t just take my word for it, here’s Sam Bowman who is far more qualified to speak on the subject than I am (I also highly recommend his article):

If all this [expensive housing and all of its n-th order negative effects] has a solution, then we suggest it is unlikely to be won through a zero-sum political ‘tug of war’… Some kind of creative, below-the-radar solution that turns this zero-sum game into a positive-sum one is likely to have a better chance. In a tug of war, it’s often surprising how far you can go if you tug the rope sideways.

Sam Bowman, The Housing Theory of Everything

This is a problem that cannot be solved by policy because at its core it is not a policy problem.

Instead, it is best approached entrepreneurially: by inventing a better system that is completely opt-in. A system that succeeds not through coercion or bribery, but by offering something that people actually want; something that gives them a better life.

It can be solved by creating a new positive-sum game.

If you read to the end I thank you for joining me on this exploration! I broke this post up into two parts: an exploration of the problem here and an exploration of a solution in the next post. See you then!

Until next time,

Joel

It occurs to me that renters e.g. in places like Manhattan and San Francisco can be just as NIMBY as homeowners in the suburbs. Both groups resist change in and of itself, while one group has an additional reason to oppose development (real estate prices), but it’s not clear to me that the absence of the latter consideration makes renters any more favorable to new development. Or am I missing something?

I like this take and set up. Usually the way I think about this problem is that it is a representation problem. Future generations are not a part of the decision making process. Or there is no way to implement a Rawlsian "veil of ignorance" in a zoning board, city council, etc. But I like your angle that it's an incentive problem and looking forward to part 2!