Good morning,

In the process of researching and thinking through how housing might work in a cooperative city, I came across some interesting ideas. Please enjoy today’s piping hot Jambalaya. The ingredients are land rent, urban economics and a pinch of solution (be careful, it’s spicy!)

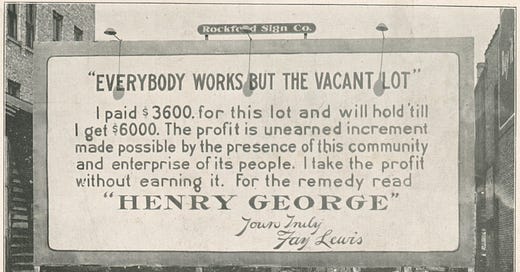

Henry George and the Land Value Tax

For a full summary of Henry George’s work, I highly recommend this book review.

George’s idea is that there are three factors of production: Land, Labor, and Capital.

He argues that other schools of economic thought have made a massive error by lumping “Land and Capital” together. Land, George insists, is not capital - it is something entirely different. It is exogenous to human society and not something we made. Its supply is fixed and the fact that land exists is not the product of human ingenuity (unlike labor and capital).

Individual humans, therefore, are not entitled to the natural value of land. The value should be distributed among all members of society.

What George is getting at is that as long as land owners are able to extract rents from the economy, they, not workers will capture most of the productivity gains that we create as a society. This, George says, is why we can progress as a society yet inequality worsens, wages stay flat, and poverty and homelessness persist. Labor gets more efficient, but the returns of that ultimately go in the form of rent to landowners.

His solution is to take the entire income of land (NOT anything built on it - an important distinction) and distribute it equally among all members of society. This has the added benefit of eliminating inefficient labor taxes which further punish individuals who make a living with their labor.

There’s a lot to like about George’s ideas. They can sound foreign to us today simply because we collectively made a choice to go down the “tax labor and capital” road instead of the “tax land” road, but check out the book review and it’ll start to make more sense.

The next question: if land value isn’t created by landowners, where does the value come from?

Land Value Factors

Why is land in some cities more expensive than others?

Urban land values account for most of the land value in the country. In very productive cities like NYC or SF, land value can come to be nearly 100% of the housing cost.

Land prices explain variations between cities in real estate values. Construction is more or less uniform across the country (it is a little more expensive to build a high rise than a single family home, but the difference is not orders of magnitude like land)

Land, however, can be thousands of times more valuable in the middle of San Francisco than in the middle of a field in Nebraska. Why is that?

There are three major factors, with one being disproportionately important. This is mostly taken from Stephen Hoskins’ great article on Land Value.

1. Nature

This one is pretty straightforward: land that is prone to flooding, hurricane damage, or other natural disasters is less valuable than land that is not. Flat sites that are easy to build on are more valuable than hilly sites that would require significant work to make building-ready.

2. Government

Also straightforward: land that gets forcefully seized by governments or individuals is also not very valuable: See Kiev real estate market.

Government actions around school location and quality, placement of parks, street design (walkable areas are more desirable and therefore valuable), and much else also influences property values.

3. Society & Agglomeration Effects

This last factor is the most important of the three.

The iron rule of cities is: people go where people are.

When people live near other people, everything gets easier and more efficient: we have easy access to dating markets, cultural and entertainment, and most importantly, labor markets. Economists call these “Agglomeration Effects”.

Remember in Econ 101 the lesson on Economies of Scale - businesses get more efficient per unit the more they produce? This is

At the foundational level, proximity – especially to other facilities and suppliers – is a driving force behind economic growth. Jane Jacobs observed this many years before economists formally studied it:

Proximity is the vital ingredient that makes all urban areas tick. It is this proximity that enables people to exchange ideas, goods, fashion, beliefs, knowledge and anything else they see fit, generating the diversity that the most valued places all share. It is when people come together that mankind's greatest achievements and most engaging environments have been realised. And it is when this proximity is diluted that the success of urban areas is most harmed.

(Meanwhile, planners in the U.S. were busy diluting America’s urban proximity)

Labor markets are the engines of the economy. Cities like New York and San Francisco became so expensive mainly because access to their labor markets was so valuable. The income people could earn in San Fransisco’s labor market can easily be multiples more than other labor markets. They were therefore willing to pay high land prices in order to access that labor market.

💡 Side note: I am also very interested in what happens now that many of these labor markets are digital. Malls used to serve as platforms to access “markets” of useful retail stores - they had their own form of agglomeration effects by clustering different things of the same type together. Then Amazon and E-commerce digitized that market. What happens when the world’s most productive labor markets can be accessed from anywhere? I don’t think agglomeration effects for labor markets will disappear entirely, but will it mean that land prices stay high and keep rising, or that they will fall when enough people decide to live elsewhere?

Landowners Do Not Create Value

The big point here is that the value of land is not created by the landowner. They may build something on it that is useful. How successful that construction is is a product of their own labor and capital, so they should enjoy all the value it creates.

But the three factors that govern their land value are either 1. out of their control or 2. the work of other people.

The crucial point is this: land value is entirely created by nature, government, and society. Urban land owners have essentially no ability to influence the value of their own land. They can simply sit back and enjoy the land rents that are created by the efforts of everyone else around them.

Stephen Hoskins, Who Made the Land Value?

Think about the role of parents. One job is to teach children the idea that their actions have consequences. What if every time they did something good you punished them, and every time they did something bad you rewarded them? They would probably not turn out very well.

“Show me the incentives and I will show you the outcome”

- Charlie Munger

Here’s some more from Stephen Hoskins on the effects this has on cities:

What’s worse is that the actors who generate this value are not being compensated for their contributions. Mason Gaffney describes how public infrastructure projects, funded by taxes “wrung from workers,” generate value which is privately captured by land owners. This process essentially redistributes wealth upwards, which is why land rents lie at the heart of inequality. This gives property owners a direct financial interest in maintaining restrictive zoning across the city, which creates a scarcity of housing, meaning that prospective homeowners must take larger mortgages than they would otherwise need to, and tenants are burdened by punitive rents.

Indeed, tenants have the worst of it under the current system. When they go to work, not only do they pay taxes on their earned income, but they must also pass a sizable chunk of their wages to a landlord for the mere right to occupy a patch of land near to that job. When their contributions to society make their city more desirable, they are punished with constantly climbing rents, which make it harder to stick around and enjoy what they’ve helped to make. “The invariable accompaniment and mark of material progress is the increase of rent”.

Again, it’s not that landowners are bad people - not at all. They are simply actors in a system that has a tendency in a certain direction. The way to change things is not to change the actors, but to change the system.

Most people agree that individuals who work hard and create useful things for fellow humans should benefit from their labor and ingenuity.

Land rent to land owners bears no relation to any value added to the economy. The value of urban land is mainly the result of economies of agglomeration - the natural product of millions of people living in close proximity and doing socially useful things every day.

The people who should benefit from that value should be the people who create the value.

The Solution

Okay, so this has been a wild ride. Where do we go from here?

To right these daily injustices, we must find ways to return land rents to the public. All humans have a moral right to share in the material wealth that was given to us by nature. Value which is collectively generated by society and through the government should be shared by all members of that society.

- Stephen Hoskins, Who Made the Land Value?

Henry George and the Georgist community today advocate for a Land Value Tax (LVT). I’m not going to get into the mechanics of how it works here (the book review linked at the beginning is part of a great series on the practicality of implementing LVT).

I am usually pretty skeptical of the ability to reform through the passage of new laws and regulations at the federal level. In this case in particular I am very skeptical that large-scale reform of this type would be possible. The current tax system is so entrenched and there are so many wealthy beneficiaries of it.

If reformation isn’t possible, what do you do?

Invent, of course.

Invention

The spirit of Georgism is to make the value of the land “held in common”. If that’s the case, could there be other ways to accomplish that? Could a solution be to skip the tax entirely?

A tax is simply the best way we’ve invented to this point to move value from certain places to society as a whole, but taxes come with their own set of problems - enforcement, assessment, and bureaucracy.

What if instead we could use modern forms of distributed ownership and actually build a city where the residents hold the land in common directly, with privately owned buildings? This is essentially what Singapore did. Technically the land was held by the nation-state - Singapore - but they behaved in many ways like a private organization, so the line between state and corporation is somewhat fuzzy.

They went from ranking near the bottom in development among nations in the mid 1900’s to among the best in the world today through Georgist policies. The United States has a more... mixed track record over that time period, particularly on social issues like housing and inequality.

Direct Ownership > Indirect Ownership

As newsletter readers know, I love exploring of “Cooperatively owned cities”. It makes a lot of sense once you understand that the value of a city is almost entirely derived from the activities of the individuals who live there. Why shouldn’t they all be the ones who benefit from the value they create?

A city where the land is cooperatively owned would be a Georgist city. The value of the land would flow directly to the individuals who live there and whose daily activities contribute to its increase in value. They would be the ones entitled to any economic rents produced by the land of their city.

Ownership would be restricted to only those individuals who reside in the city, prohibiting speculation. Ownership would be fractional, meaning it would only cost a few dollars and be open to all.

Developers would construct buildings under long-term ground leases from the city (similar to Singapore). Who gets the revenue from those land leases? The city owner-residents, of course.

This incentivizes the individuals living in the city to build as much new housing as they can (Solving the NIMBY problem) and incentivizes them to invite economic activity there.

Make no mistake, this city would be competing directly with every other city in the United States for residents, so it better offer something compelling. This model would offer every resident the ability to directly contribute to and benefit from the wealth of their city. I believe it would be particularly appealing to individuals who work remotely, are frustrated by the poor management and housing costs of major cities, and who played too much Sim City when they were young.

Technological invention is important. Just as important but very often neglected is social invention. We need new social technologies just as much or more than we need new physical technologies. Hegel was right: we must reform old institutions thoroughly but gradually. We need a new trajectory for the development of our institutions, not a top-down shock. We need to build and evolve new institutions, not tear down old ones.

I don’t know if this is the optimal model. But it seems to address many of the problems that cities struggle with today, so isn’t it worth a shot?

Next Steps

To summarize, I think Henry George’s ideas are interesting and worth taking seriously. Where I differ from the mainstream Georgist crowd is where to go from there.

America has always been about invention. Individuals who think something can be done better than it’s being done now should go out and try to build something better.

This sounds far fetched when speaking in terms of cities - you can’t just start a new one! Today, it’s really not that far fetched. Labor markets are increasingly digital. Tens of millions of Americans are extremely mobile now - with no need to live in New York or San Francisco to access those labor markets. And you don’t need millions of people to start generating agglomeration effects, only a few hundred passionate people to start with.

The city can’t just be in the middle of nowhere. It would need to be nearby but not in an existing municipality with sufficient demand for housing to get started. But it would not take long for it to become an economic engine in its own right.

Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is

The best way to disagree is to build. This idea of resident ownership is something we’re addressing right now, albeit at a smaller scale, in our neighborhood center here in Florence, Alabama.

Most of the neighborhood will be resident and small business owned. To me, that seems the only way to ensure long term neighborhood health and prevent gentrification or disinvestment. The best way to give people a sense of ownership is to...wait for it... make them owners!

It is a small scale acknowledgement that the people who make the neighborhood desirable - the residents and the small business owners - should capture that value.

Thanks for reading! Until next week,

Joel

Just subscribed a few days ago and came across this one. I like your framing of this. A lot of folks see harberger taxes as the solution to this but it seems like you are going after a slightly different model. Excited to see where you go with it!

Brilliant. I have been thinking about institutional investors buying up properties in cities in which they do not live. Why? What effects will that potentially have on labor investors in this ‘newish’ vision.