Joel's Jambalaya #6 - Cooperative Cities, Part 3

Revenue Maximization and the Organic Growth of Cities

Intro

Welcome back to Joel’s Jambalaya!

The last few weeks I’ve been exploring a topic that I’ve grown fascinated by: cooperatively owned private cities.

Today, instead of a deep dive into one aspect of this idea I’m going to look at several different elements of a city and think about what impact this new model might mean for it.

Some of the questions I’m asking are:

How will this model differ from traditional models of municipal governance and management?

What advantages could it offer residents?

What economic effect will it have on its residents?

Let’s jump in!

City Management

A great point from a Jambalaya reader and fellow Substack writer Fei-Ling Tseng is that housing cooperatives often struggle with management. This doesn’t surprise me at all. Think of the HOA horror stories we've all heard (or experienced). When people who don’t know what they’re doing come into power, things can become unproductive very fast.

This is a question of scale. A cooperative at the scale of an individual building is too small to be able to afford a full time professional manager or management team. But housing cooperatives today don’t scale well beyond a single building. This sticks them in an awkward spot: too small to pay for professional management, but often big enough to need it.

A cooperative city would operate more like a modern day corporation. Cooperative are a type of ownership structure, but beyond that can adopt well-proven management structures. It could go something like this:

Owner-Residents elect a board of directors to represent their interests. The BoD would be comprised of significant owners and preferably residents.

The BoD hires a management team, starting with the CEO to run the operation. The CEO then hires the fills out the rest of the management team. Some important positions would mirror those in a company today:

CFO - Responsible for budgeting, financial controls, cash flow

Customer Service/satisfaction lead - Ensures needs of residents are met through continuous surveying and data analysis

COO - Ensures the city runs smoothly, overseeing the heads of specific service departments like trash, utilities, etc.

The difference from municipal management today is that management would be accountable to people who have ownership in the city. I know, in theory city officials are accountable to residents of today’s cities. In practice, however, there is often very little recourse for citizens to get officials to act.

(And one important note: the problem with companies is usually not their management structures, it’s their ownership structures. I explore this more in next week’s issue.)

Management’s KPIs

We’ve all heard Peter Drucker’s famous dictum: “What gets measured gets managed”

What do cities measure today? I really don’t know. Debt service? Tax revenue? I don’t know of any city that explicitly tracks and manages for the well-being and satisfaction of its residents in a holistic way (If there is an example I’m not aware of, please let me know!)

A city is a general-purpose platform. It exists as a place where individuals are free to pursue whichever ends they find personally meaningful. The city’s management team should be hyper-focused on how to provide this general-purpose platform in the best way possible.

Instead of focusing on a single or handful of metrics, why not track a broader set of metrics in a public dashboard?

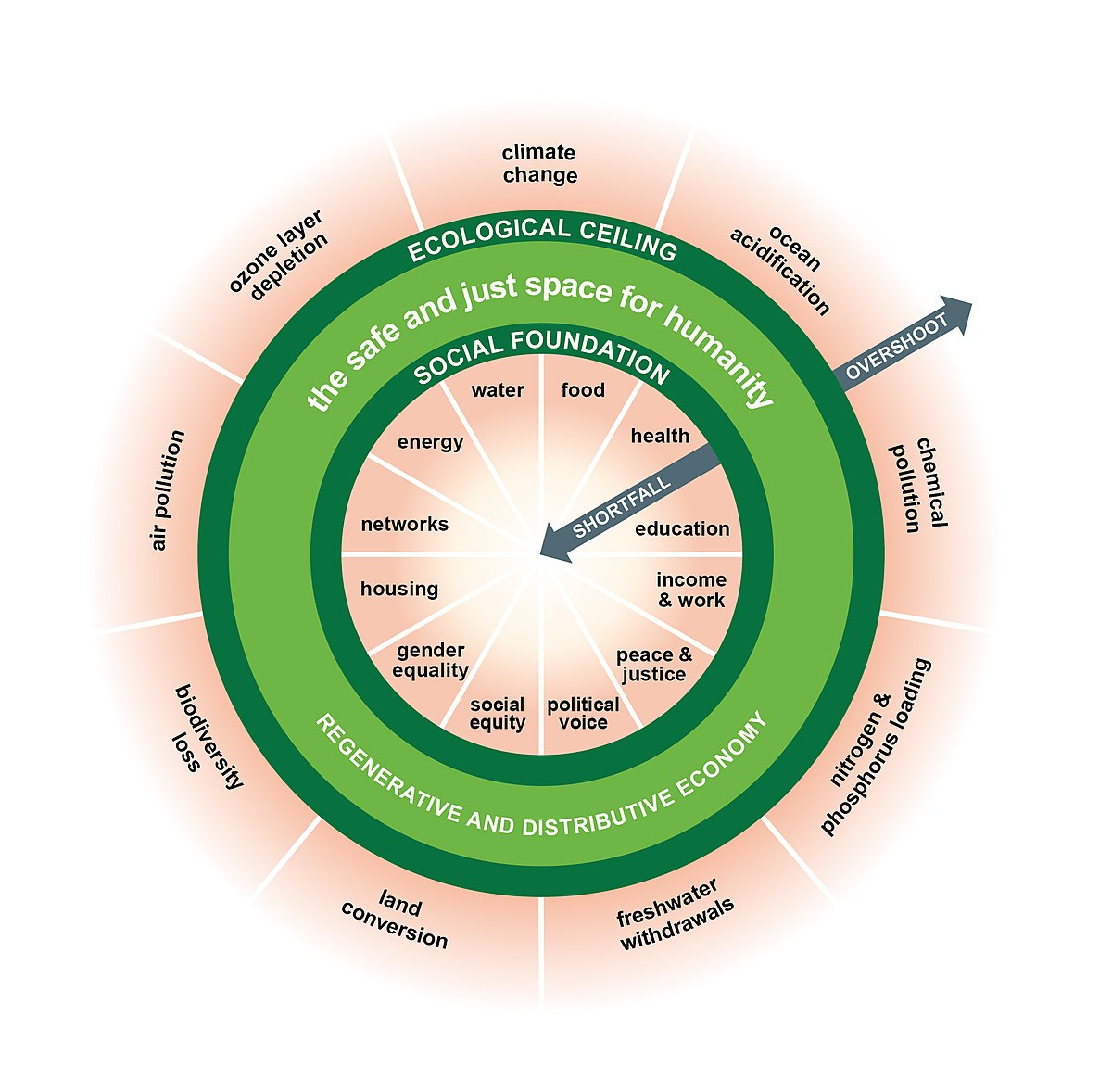

The model below is Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, which seeks to provide a broader measure of progress than the ubiquitous GDP. It serves as an interesting starting point to think about how to serve residents in a more well-rounded way.

The appointed management team would face the upside of good management decisions and the downside of bad ones. Their pay (set by the Board and visible to residents) would be tied to relevant metrics:

The head of electricity would be measured based on uptime, time to process new service, etc.

The CEO would be paid based on an overall measure of resident satisfaction

The COO would be paid based on some measure of value of services (cost relative to service provided for all his or her departments)

These measures would change over time as the size and needs of the city change.

Today, city management teams face downside for bad decisions but no upside for good ones. This leads to a lot of ideological mumbo jumbo (like doing things in the name of the “common good”), but not much actual progress.

The solution to problems of misaligned incentives: make sure the right people have the right amount of skin in the game. This is something good parents understand that many institutions seem to forget: people have to face the consequences, good AND bad, of their decisions. If they don’t, everything goes to shit.

This management structure would make a choice: to accept that managers will occasionally make mistakes. But this is the right thing to do, because the costs of bureaucracy are hidden but much higher. Here’s the O.G. organization builder, Warren Buffett, explaining why he trusts his managers with autonomy:

“We would rather suffer the visible costs of a few bad decisions than incur the many invisible costs that come from decisions made too slowly — or not at all — because of a stifling bureaucracy.”

Revenue

How might we rethink revenue policies if we’re reimagining the city from the ground up? Cities are notorious for several fiscal miscues:

Underpricing & undermonetizing valuable assets.

Delivering essential services at high cost/low value.

Doing infrastructure projects only because the funds are available from the federal government.

Further, many municipalities (at least in the South) live or die by sales tax revenue. This has lead to the overbuilding of suburban retail space to an astonishing degree.

Back to my favorite Charlie Munger quote:

Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome

Show me a city funded by sales tax, and I’ll show you a city with 3 Walmarts. These cities had little choice but to grow in a sprawling, unsustainable way. The only means they had to provide services was to keep incentivizing big retail establishments to move to town, often to the exclusion of much-needed housing.

A city based on balanced revenue sources would grow in a more sustainable way. It could rethink how it raises and spends funds. It would be sure to grow in a way that doesn’t bankrupt it decades down the road. There are lots of interesting ways for cities to do this, but rethinking tax schemes is the most interesting.

New tax Schemes

Switzerland has an interesting model. A flat, $50,000 per year tax for anyone wishing to move there and have access to public services. This is based on a very simple idea: the marginal cost to service additional users of public services is well below $50,000 per year. As long as marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost, this makes sense.

I am interested in what a similar model could look like here. Instead of a percentage of sales, the city could levy a flat tax across all residents. After all, how well does sales tax revenue match the cost of providing public services?

Perhaps even more interesting, some city services could be offered a la carte, allowing residents to choose and pay for only what they need. In this scenario taxation in the city would become more like a subscription fee in exchange for services than a tax. (Don’t worry, I’m not going to start saying things like “Municipal Services as a Service - MSaaS - there are enough “as a service” acronyms as it is)

No matter the exact tax and revenue regime, there are two important differences between our imaginary co-op city and today’s municipal models.

First, every resident of the city would also be an economic interest holder, entitled to the residual value of the city after it has provided essential services. This would encourage parsimony by the city management team and discourage administrative bloat.

Second, residents of this city are completely free to leave any time they see fit. This further discourages exploitative taxation practices. It is more like a subscription than a tax - cancel when the service sucks.

Alternative Revenue Sources

Further, entrepreneurial management teams would do a much better job of accessing alternative revenue sources on behalf of their residents/shareholders.

Cities often have tremendous assets lying dormant or underutilized. If management teams can find ways to use those resources more effectively - by adequately charging nonresidents for their use of resident infrastructure, for example - it represents new wealth that flows directly to the resident-owners.

Similarly, management would be incentivized to partner with external developers to bring interesting new real estate to the city.

City Planning

Our imaginary city would explicitly acknowledge and use the fact that cities are organic, living organisms. In a recent newsletter, Fei-Ling Tseng wrote about the idea of simple proscriptive and prescriptive rules to design complex systems. She uses the game of Townscaper as an example of how very simple rules create complex, organic products:

The city will not be planned in any conventional sense. The only things specified up front are distinct neighborhood centers and public buildings with the beginnings of a street network laid out.

Each neighborhood might specify up front specific form-based design guidelines to give it a distinct character. Imagine one neighborhood with predominantly Greek Revival architecture, another Mid-Century Modern, and so on. This helps humans delineate separate parts of the city, including their own neighborhood. Contrast this to most real estate built today: it looks like it could be anywhere and has no identity of its own.

After the simple rules are decided, growth of the city would be the outcome of individuals building within the rules like in Townscaper. The result of this bottom up approach are complex, beautiful designs that emerge naturally and could never be planned. But how would we visualize and manage the growth of the city?

The Map Layer

To grow in this way, there needs to be a way for people to browse and design real estate in real-time. In our new city, there would be an interface layer similar to town-building games like Cities: Skylines or Sim City:

This serves as an interface layer for all residents, builders and service providers to interact with the built environment.

The user enters the map and can explore the city, zooming in and out of different areas and viewing the city at different scales. It's like playing SimCity or browsing Google Earth. Prospective residents would choose a neighborhood, zoom in to view available building pads, design their property in a Sims-like interface (or select from a preset model), and purchase it through the app.

The map would update in real time as users commit to designs and construction. Even before construction is complete, people can watch the growth of the city live. Crucially, the city would grow over time as individuals build according to simple rules such as:

New structures must be adjacent to an existing structure (no buildings alone in a field)

No more than four stories

Depending on neighborhood rules, maybe some guidelines around materials and form - must have a certain type of roof, or certain architectural features

In this scenario, the city planner would not really be a planner. They would be a steward, watching the growth happen and ensuring the organism (the city) has the resources it needs to grow.

It would be the opposite of today’s cities. Most create a 10-30 year plan of what the city will look like in 30 years and plan out how it will grow into that final form. Here, there would be no formal “plan”, only a simple set of rules that individuals design within.

The rigid, single-land-use planning model used today kills the natural, evolutionary wisdom of cities. As Fei-Ling Tseng puts it:

Modern city-building practices have largely scrapped the ancient, emergent ways of building cities in favour of zoning and other overly-prescriptive rules. To adapt our prescriptive rules to local context, our zoning codes grow more and more complicated requiring vast amounts of exceptions and administrative work every time someone wants to make a change to their property.

It is ironic that North American cities don’t allow for more rule-based, emergent urban development. Real estate needs of the market could be addressed more dynamically and on an ad-hoc basis, compared to the current regime in Toronto and other places like San Francisco, which is too restricted by law to be market-driven.

Fei-Ling Tseng, “The Beauty in Simple Rules”

Cities are made up of physical elements: streets, buildings, utility infrastructure. But they are not physical things.

Cities are living, breathing organisms. Cities should evolve. They should be grown naturally, not manufactured according to a blueprint.

This issue is already longer than I had planned, so I’m going to stop here for today. Next week we’ll get into the weeds on how the new model would impact residents economically. See you then!

Joel